The opening of Neal Bell's "Two Small Bodies" at

the Matrix Tuesday is yet another example of how far the theater's

management will go to do right by a play. Producer Joe Stern first got

wind of it at the O'Neill Playwrights Conference in 1977, then heard

of a subsequent production at Playwrights Horizon, "and finally got to

see it on its feet at an outfit called the Production Company in New

York.

"Its something I've wanted to do for a long time,

and even turned down a couple of two-character plays, such as These

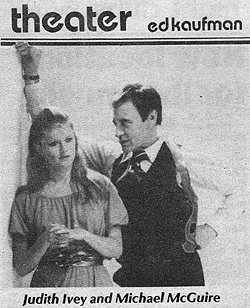

Men,' in order to do it," said Stern. "I had Michael McGuire in mind

for the male role, but it wasn't until I saw Judith Ivey in the New

York production that I knew we (meaning Actors for Themselves) had the

right actress. Before that, I held onto the play for 16 months. That's

how much I think of McGuire."

The upshot of it is that both Ivey and director

Norman Rene, who runs the Production Company, are coming out to do it

again. That may not be news on the commercial circuit, but it is a

tribute to the drawing power of Equity Waiver for artists.

"I really only came out to do this play," said

Rene, "not to put out feelers into television and the movies. New York

is slow this time of year, and I wanted to stick with a play I think

is unique in its insights and emotional impact.

"The play is loosely based on the Alice Crimmins

murder case, in which a cocktail hostess murdered her two children.

Ivey plays the hostess and McGuire plays a detective who's

investigating the case and strikes up a personal relationship with

her. To me, the play says an awful lot about the prejudices between

sexes and classes, the old baggage one brings into new relationships,

and the lure between a mother-hooker figure and a policeman who's

reconceived in her mind as a father figure. I think in terms of

language and texture, and in the way it deals with the complications

between men and women, that it's a fascinating work."

Rene is also the person who conceived and directed

"Marry Me a Little," which brought to light songs that were dropped

for one reason or another from Stephen Sondheim musicals. A production

is still running in London (it played last year in New York). Maybe

Stern could coax Rene into doing it here.

REVIEW: VARIETY, Thurs, Sept. 16, 1982

Actors for Themselves' second entry into its

current two-play repertory, "Two Small Bodies," by Neal Bell, is yet

another version of an actual case in which a promiscuous mother is

accused of murdering her two children and her seeming in-sensitivity

to the matter complicated the investigation.

Bell's rendering of the tale is chilling in itself

and director Norman Rene mounts it on a cold, representational set

that emphasizes the personal tragedy. Gerry Hariton and Vicki Baral

have seen to the set design and made it particularly stark.

Judith Ivey, who originated the role of the mother

when show preemed at Playwright Horizons in New York, is repeating in

her role and Michael McGuire is playing the policeman who is

alternately disgusted and fascinated with this unemotional woman.

In a series of short scenes (almost cinematic in

nature, but not as effective), story unfolds that, although she didn't

kill the children, she is guilty of sometimes wishing them dead, as

they got in the way of her hedonistic activity.

Ivey plays the role of the unsympathetic sybarite

with an absolute remoteness and verisimilitude. With a stoic attitude

toward the detective, the slightest deviation reveals the pain she is

actually suffering at the somewhat sadistic handling of the

interrogation by McGuire.

Latter plays the detective straightforward, and his

unswerving approach to the probe heightens the torture the girl

endures. The lust he begins to feel for her reduces them both to the

animal level. But it also reduces the show to a plane of cold, hard

fact which is more difficult to digest than fiction.

The work being done is a masterful production, but

the audience has to work to become involved. There's an undercurrent

running through the play that makes the viewer feel that he wants to

sympathize with someone. But when that feeling starts, he is made to

feel unwelcome. A strange and intriguing type of play that never gives

itself to the audience.

There's an invisible wall between the characters

that extends beyond the proscenium and keeps the audience at a

distance. It's as if there's a sign warning: "Look, but don't touch —

or be touched."

Mary I. Gleason's costumes are quite good as are

Hariton and Baral's sets and lighting.

REVIEW: L.A. WEEKLY, September 3-9, 1982

by Joie Davidow

A few years ago, New Yorkers were intrigued by the

sensational details of the Alice Crimmins case, which ran in the daily

papers for months. Playwright Neal Bell exploits the same macabre side

of human nature that makes crime headlines sell newspapers in this

two-character play, based on the Crimmins case. Alice Crimmins was a

cocktail waitress, accused of murdering her two children. Bell sets

aside the nasty issue of what kind of a rotten lady kills her

own kids — actually, he seems to suggest that anybody could do it if

they got mad enough. Instead, he fantasizes on the relationship

between Crimmins and the investigating detective, concerning himself

with the tension between man and woman — the power trips, the

obsession, the tentative attempts at communication, the hasty retreats

back to game-playing. He does it through a series of blackouts, at

first very short scenes, then longer ones, and he uses every easy

trick: she takes off her clothes, he takes off his clothes, dirty

talk, violent talk. At one point, she asks him, "What are you gonna

have to do to make me react?" It's the same approach Bell seems to be

taking with his audience.

But what makes the evening interesting — very

interesting — is the work of actors Judith Ivey and Michael McGuire,

directed by Norman Rene. Perhaps the best thing that can be said for

Bell's work is that it challenges the actors and gives them a chance

to show off. These two are more than up to it — creating real

characters, taking them through a range of emotions. It's a

fascinating display of acting skill, which is nearly enough to sustain

one through the relentless pessimism of the play.

REVIEW: DRAMA-LOGUE, September 2-8, 1982

Reviewed by Lee Melville

First of all, one has to accept that Neal Bell's

Two Small Bodies is not logical; otherwise, you come away from a

performance with too many questions for which no answer is provided or

can be concluded. Two Small Bodies is an abstract jigsaw puzzle

where the pieces do not fit. It makes an interesting companion piece

for Harold Pinter's Betrayal with which it splits the week in

performances at the Matrix Theatre where both are being presented

under Joseph Stern's Actors For Themselves banner. Whereas Betrayal

is perhaps Pinter's most logical play —finely crafted with every

line filled with meaning — Bell's play is loosely structured with its

dialogue taking on dark, ominous meaning — or is it all a fantasy?

Eileen Maloney's two small children are missing.

Kidnapped? Murdered? By whom? Perhaps by her husband. Perhaps by her.

Lt. Brann seems to believe she did it and in a series of

interrogations tries to break her down to a confession. If it is based

on the well-known Crimmons case (in New York), it never fully commits

to a resolution. Obviously, that is Bell's intent. Lt. Brann, father

of two boys, is a straight arrow police officer who gets "wrought up"

by missing child cases. Eileen is a cocktail waitress who feels "being

a mother can be a rather tiring thing;" her children crowd her. Do

these different attitudes cause the negative attraction toward each

other as they engage in a sexual tug-of-war? Could be. Or does each

represent a fantasy to the other? Very likely.

You're not apt to find cleaner, more solid acting

anywhere than in the performances of Judith Ivey and Michael McGuire

as they turn these rather ill-defined characters into real people.

Through Eileen's hard, brittle exterior Ivey illuminates the

vulnerability inside; if, at times, she seems too forced, it is

exactly what Maloney would do. McGuire gives a simple lesson in

responding to another person; he receives what Ivey emits with

understated honesty. There is not one false moment in his precise

portrayal of a man grasping and, at the same time, losing his grip on

reality. One is not sure what the term "actor's actor" means anymore

but if it is someone other actors can appreciate, study and gain from,

then McGuire is the epitome of that.

There is a third character in Two Small Bodies

— the lighting design of Gerry Hariton and Vicki Baral. Nothing

more is needed onstage to convey time, mood and place. If lighting was

always this exciting it would not so often be the overlooked child in

the design family...

One can disregard the flaws because they are minor

in view of the major breakthroughs Two Small Bodies achieves.

This production should be seen primarily for the acting which Stern's

company again attests to how exciting good theatre can be.

REVIEW: EVENING OUTLOOK, August 27, 1982

Two misfits who meet

by Ed Kaufman

At

first, "Two Small Bodies," currently in its West Coast premiere at the

Matrix Theatre in West Hollywood, seems conventional enough. A routine

investigation of a couple of missing children. Asking all the

questions is a tough, no-nonsense New York cop, and answering the

questions is the equally tough mother of the two children.

At

first, "Two Small Bodies," currently in its West Coast premiere at the

Matrix Theatre in West Hollywood, seems conventional enough. A routine

investigation of a couple of missing children. Asking all the

questions is a tough, no-nonsense New York cop, and answering the

questions is the equally tough mother of the two children.

So far it looks and sounds like TV fare: the

exhausted cop and the flippant mother. Only it's not. Author Neal Bell

has used the conventional format of the "investigation" to go beneath

the obvious and the routine. As a result, "Two Small Bodies" becomes a

psychological whodunit and a study of attitudes and relationships.

Author Bell has managed to capture a mixed-up world

with a sort of street poetry that often soars. Certainly it sears, as

the two characters try to get their emotional bearings in a sea of

change and uncertainty. And it's no longer a question of increasing

violence. Every generation has had violence. It's a matter of how we

react to it, and the value system that gives life meaning to offset

all the craziness.

What makes "Two Small Bodies" so strong is its

attempt to find a sense of shape in the world. Shakespeare might have

looked for a system in the heavens. Author Bell never looks up from

around the apartment of Eileen Maloney. If there's an answer, it's

tentative and, perhaps, written in the wind.

Eileen and Lt. Brann are a couple of misfits. She's

a cocktail waitress, a high-priced hooker, a woman who's a mother and

who feels "crowded." And she's also full of confusion and guilt.

Brann's a New York cop, a realist, at times abrasive, a relentless

pursuer of facts. He's also vulnerable and a pretty decent family man

trying to cope in a world of sham.

The two meet ("collide" would be a better word) on

the white, austere set of Gerry Hariton and Vicki Baral, who also

designed the effective lighting to silhouette a couple of characters

struggling with the "truth": the facts of the case and the emotions

within each of them.

Judith Ivey and Michael McGuire are absolutely

stunning as Eileen and Brann, whose star-crossed world brings them

together. Both are allowed the actor's right to touch all the

emotional bases. Ultimately there's a sort of understanding that comes

from emotional exorcism.

REVIEW: DAILY NEWS, September 27, 1982

'Bodies': a Mystery of the Mind

by Rick Talcove

In Neal Bell's stark drama, "Two Small Bodies," a

detective and a would-be murder suspect go "one on one" in a series of

interrogations that often make you to wonder who is captive and who is

captor. By employing a technique that boldly eliminates all theatrical

waste, this latest production by Actors for Themselves at the Matrix

Theater in Hollywood achieves a formidable success.

Theatergoers may notice a distinct similarity

between the character of Eileen Maloney in "Two Small , Bodies"'and

Claudia Draper, the heroine of "Nuts." Both women are hard-living,

hard-driving examples of soiled femininity, with constant chips on

their shoulders.

But where "Nuts" concentrates on whether Claudia is

sane enough to stand trial for a crime she obviously committed, "Two

Small Bodies" (suggested by a true incident) presents the mystery of

whether Eileen Maloney actually killed her two small children,

sleeping in an adjoining bedroom.

Lt. Brann, the investigating officer assigned to

interrogate Eileen, has his reasons for being alternately repelled and

fascinated by this woman. She represents a heartless, selfish,

sarcastic female who nevertheless brings out a long submerged passion

in him. Like Martin Dysart, the psychiatrist in "Equus," Brann is

drawn to this woman sexually for the very things that disgust him

emotionally.

Ultimately, through the clever game-playing

each character employs upon the other, the solution to the mystery of

"Two Small Bodies" is adroitly solved. This is not an Agatha Christie

tale of false moves and unmasked motivations; rather, it is a tightly

coiled mystery of the mind and how human beings can be dedicated to

their own self-destruction.

But, above all. "Two Small Bodies" is a fascinating

piece of theater.